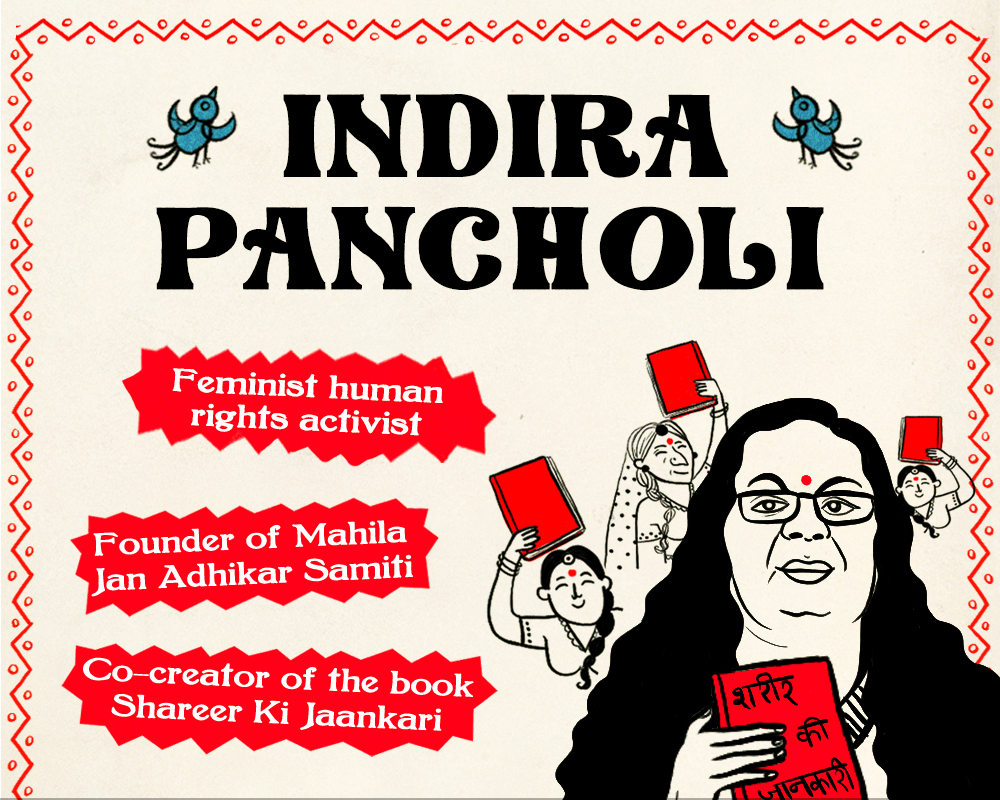

Indira Pancholi is a feminist-human rights activist. For over 25 years, she has worked with children, adolescents, and women from rural and urban areas in a variety of social issues. She is also the founder of Mahila Jan Adhikar Samiti (MJAS) - a women-led organisation advocating for women’s rights and greater gender equality.

In the 1980s, Indira Pancholi was part of the team that made the path-breaking book Shareer Ki Jaankari or as it was popularly known Lal Kitaab. Published by Kali for Women (now Zubaan), this illustrated book discusses women’s bodies and sexuality. In this interview, Indira shares the story of why and how the book was made, how it reached the people it was made for and how feminist movements have changed over the years.

Could you tell us a little about the context in which the book Shareer Ki Jaankari was made?

Around 1986-87, the government ran this program called the Mahila Vikas Karyakram (MVK) under the Women’s Health Department. This was one of the relief programs to address the widespread famine at the time. People were leaving villages in search of jobs all over.

I joined the IDARA wing (Information Development and Resource Agency) of the MVK. Now, this program was funded by UNICEF and was unique because it also involved the citizens in carrying out the relief program. A health campaign started to raise awareness about women’s bodies and to help them understand the rights they had over their bodies. In it, we were discussing labour rights, right to food, work and all of this as connected to health.

Through the years, as we spoke to women in the villages we worked in, we realised there was a gap in the language that the state was talking to them in and their own everyday language. It was following these conversations that we eventually came up with the idea of making Shareer ki Jaankari this book about women’s bodies and sexuality.

How did the content of the book get decided? The content of Shareer Ki Jaankari?

We would have many workshops with the women. Many topics would get discussed there! We also asked the women how they would express their ideas through art. Then, we took those images, modified them a little and tried to incorporate them in the book. If you see the art in the book, they are like the traditional paintings you see in Rajasthan. They look very lively.

The language used is very simple. Beside the information, we made some notes asking women to reflect on their own lives, bodies and sexuality, asking them about their own experiences. You see, these women we worked with were working 17-18 hours a day at home or work and had no time. When the book was getting made, they got busier. So, whatever information was in the book, we tried to tie it to personal experiences as much as possible so people could deeply engage with it. Only then would it be possible to think of rights and all that. If our thinking doesn’t go that deep, imagining and demanding for rights is difficult.

And, how did the shape of the book - the idea of the flaps - get decided?

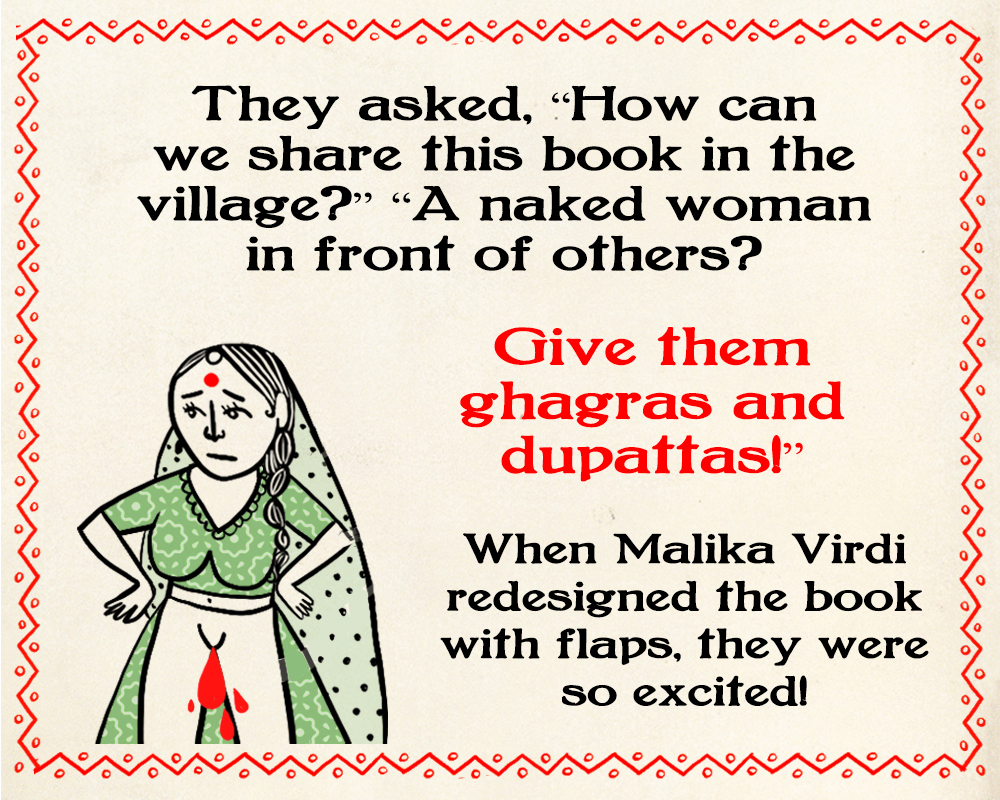

Yes, it has an interesting story too! When the first version of Shareer ki Jaankaari was ready, the women actually rejected it because of pictures of naked women. They’d ask, “How can we share this book in the village?”, “Does it look good to have a naked woman in front of others? Give them ghagras and dupattas!”

For them it was only logical. You have the ghagra outside. When you lift the skirt, what does it look like? Then when you cut through your skin what do you see? Then we explain the process inside the body – menstruation or whatever. When Malika Virdi redesigned the book with this feedback, the women were so excited with the flaps and just jumped with joy! They really loved it!

Could you tell us about the women you were working with?

All of us in the movement were working in different sectors. We would say ‘women and education’, ‘women and work’…but for the women we were working with, everything in their life was connected - employment, getting beaten by their husbands, how to keep the house running, societal relations, all of it. People would say education and work were separate from women’s issues but the entire feminist movement was challenging that idea.

When we started this initiative called the Mahila Jan Adhikar Samiti, we realised that the women in the villages spoke about sexuality very differently. We were using a very upper caste context. Their concern wasn’t sexual purity at all, but marriage was important. In fact, they had a saying there that when the wind blows, you can’t escape its touch - meaning if you are attracted to someone, you can’t help but feel inclined to act on it. But, there were caste lines to be maintained. You couldn’t run away or cross those boundaries.

So, when we were thinking about how to oppose the different kinds of violence the women were facing – from their homes, the society or even the state - and also talk about sexuality, we realised that sexuality was something that was strongly tied to marriage. And if women discussed these things outside the home, then they would be doubted. In fact, the initial imagination of Shareer ki Jaankaari was that it would be like a biology textbook.

You once said Shareer ki Jaankaari was also a way to bridge the gap between the state and the people. What response did it draw from the government?

At the time when the population control program was being rolled out, the State had managed to get an approximate list of all the couples who were eligible for forced surgery. They had identified which women had to undergo surgery. There was tremendous pressure on the women. Now, as far as the book was only giving biological information, they were okay.

But, the book has so much more. One, it talks about things right from childhood to old age. It talks about when and how women enjoy sexual pleasure, what can hurt them, the positions for all this, things like that. For example, if you see one of the images, the woman is on top of a man. It was so common for a man to be on top, that Malika [Virdi] suggested we reverse that. It was such a subtle change but it was called out.

The State started having a problem with the parts of the book that talk about what the woman wants. Even with reproduction, we spoke about how the woman could decide if she didn’t want children or how many children she wanted. She can also decide to what extent the State can interfere in her life. Also, sexuality was considered obscene. It was corrupting women and disrupting social order and culture.

So, did the book ever face any major backlash from the State?

Around 100 copies of the book were distributed in every village. All of them were collected and kept in the local Women and Child Development Department under the District Collector’s supervision. The Mahila Vikas Karyakram and the Women’s Health Department were under a lot of pressure. They couldn’t oppose anything.

The workshops and saathis’ meetings had been stopped. In the collector’s office, these collected books were burnt. I was there myself when they set fire to the books. There were even personal threats, and people were asked to leave the district.

How did the book still reach people? What happened after these incidents?

Some of us left the organisation and took the Lal Kitaab (as we had begun to refer to it) to Kali Books. Kali was a feminist organisation like us. We didn’t negotiate much or pay anything. We weren’t given any royalty either. Publishing was new to all of us. Within the feminist movement things worked on the basis of trust. The only thing we told Kali was that we had a plan for a three-book series and the Lal Kitaab was the first.

They did all the marketing for the book to be sold. We got some free copies – 50 or so. The rest we purchased. We raised money, bought the books and distributed it free of cost to the women. They gave whatever they could – 2 rupees, 5 rupees. The book was cheap. About 11 rupees. Then it became 14.

But, many years later, I went back to the same area [where the books were burned] to work on another case. There, in a meeting of over 60 anganwadi and health workers, I see them all holding the Lal Kitaab. I asked them “How come this book is here?” and they said it was part of their training material! UNICEF had distributed about 10000 copies. Just imagine!

At that time, I realised that when any change has to take place, someone has to be there to bear the brunt of the opposition to that change.

What about men? Were they reading Shareer ki Jaankaari? What was their response?

Men used to have these made-up ideas that women don’t openly share their thoughts, that you can’t understand what’s in their mind and what they’re saying. So even if women openly told them what they enjoyed or not, there would be doubts about where the women learnt all this from, if there was a relationship elsewhere. This is why women wouldn’t initiate the conversation around pleasure.

Within the workshops, as the conversation around women’s bodies and sexuality began to include scientific ideas from the book, when it began to include rights, the women took the book back home to discuss with their husbands and help them understand too. If there was some positive response or an interest, they would ask us or maybe ask for a male volunteer to talk to the men.

And men wouldn’t openly ask questions, they just wanted to know things. If a woman was with a man, she’d say explain this, explain that. So, whatever the women wanted to convey to their husbands, they used that moment for that. They wanted the men to listen to what they wanted.

Today, we may feel that the book did not include transgender or intersex or other queer identities. But, when you were working on it, did these conversations come up?

It isn’t that we didn’t talk about these things. At that time, bringing up these issues was hard. After a very long time, the State had given space for these conversations. We understood that if we talk about these things openly, then there will be immediate backlash. We feared that.

Amongst us, of course there were saathis who identified themselves with sexualities besides heterosexual, in live-in relationships. There were such women in the village too. There were extra-marital relationships or relationships besides marriage that they would secretly have. They would say that if nobody is at home and you cooked and ate something and washed the dishes, who would get to know? Eat your food and be happy, no? In the villages, even the elders had no objection to this as long as you kept it a secret.

So, we have subtly left room for these conversations in the prompts [in the book] to reflect. I do accept that labels for other sexualities and genders came later because it was part of our newer understanding. It wasn’t there when we began all this work in the late 80s-90s. It’s been 30 years now. Recently, in the last 10-20 years, there is an understanding of these things that has come to light and people are talking about it more openly.

You have had a long journey with sex education and reproductive justice in the feminist movement. What do you think has changed in these years? What do you feel needs to change?

First, it is true that without a planned health program and an experienced team, we couldn’t have done what we did. But between that time’s work and the present, I do feel there is a gap. The information flow has increased, of course. But to tie all of that up to women’s experiences, young girls’ experiences, understanding its implications, to create a community, these I feel are lacking today.

Many groups talk about community, safe space but how do they make it, where do they make it? For example, home may not really be a private space for women. In the villages we worked in, it was common for family members to come and sit with you during a workshop. It’s about finding a way to include them also, make them part of what you’re doing and ensure they understand your work and not dismiss it. That way you have more people to support you. With the internet, it can be as empowering as it is dangerous. It is necessary to connect with and understand technology. But community is irreplaceable.

Second, today we are working with different age groups of people. In the Lal Kitaab also we talk about age groups but there is the aspect of generationality, of continuity from childhood to adulthood. But today we focus on age groups as different sections.

Child rights’ groups, women’s groups, adolescent groups, youth groups - it is important for all of them to raise their voice but if we get divided so much then we won’t be able to challenge the larger system. Patriarchy, masculinity, the social system and its norms, the state – to challenge this entire larger structure, it is important we look at all these issues collectively. In isolation, we won’t be able to go ahead much.